New project: Development of integrated in vitro and in silico methods for predicting the effects of chemicals on fish reproduction

A new project between the Mechanistic & Integrative Toxicology group led by Dr Luigi Margiotta-Casaluci (King’s College London), Professor Christer Hogstrand (King’s College London) and the AgTech company Syngenta has started.

Building up on previous research carried out in our laboratories, in this project we will focus on fish reproductive toxicity and will develop novel testing strategies (i.e. New Approach Methodologies, NAMs) based on cutting-edge in vitro methodologies (e.g. high-content imaging of single cells and organoids) and computational modelling (e.g. toxicokinetics/toxicodynamics) aimed at predicting the chronic reproductive toxicology hazard of pesticides without using animal testing.

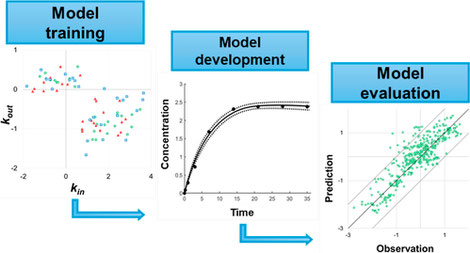

A User-Friendly Kinetic Model Incorporating Regression Models for Estimating Pesticide Accumulation in Diverse Earthworm Species Across Varied Soils

Existing models for estimating pesticide bioconcentration in earthworms exhibit limited applicability across different chemicals, soils and species which restricts their potential as an alternative, intermediate tier for risk assessment. We used experimental data from uptake and elimination studies using three earthworm species (Lumbricus terrestris, Aporrectodea caliginosa, Eisenia fetida), five pesticides (log Kow 1.69–6.63) and five soils (organic matter content = 0.972–39.9 wt %) to produce a first-order kinetic accumulation model. Model applicability was evaluated against a data set of 402 internal earthworm concentrations reported from the literature including chemical and soil properties outside the data range used to produce the model. Our models accurately predict body load using either porewater or bulk soil concentrations, with at least 93.5 and 84.3% of body load predictions within a factor of 10 and 5 of corresponding observed values, respectively. This suggests that there is no need to distinguish between porewater and soil exposure routes or to consider different uptake and elimination pathways when predicting earthworm bioconcentration. Our new model not only outperformed existing models in characterizing earthworm exposure to pesticides in soil, but it could also be integrated with models that account for earthworm movement and fluctuating soil pesticide concentrations due to degradation and transport. (link to paper in ES&T)

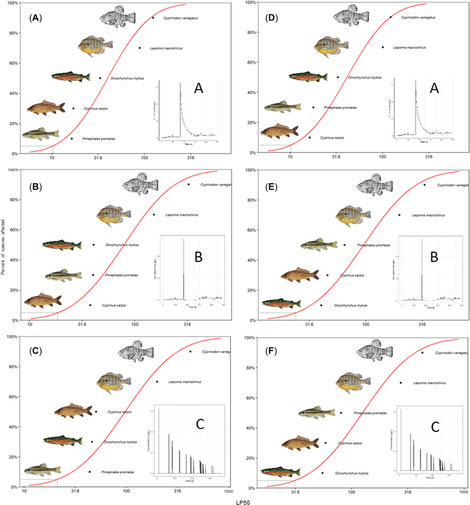

Fish Species Sensitivity Ranking Depends on Pesticide Exposure Profiles

It can be expected that the sensitivity of a species to a substance is dependent on the interplay of TKTD processes with the dynamics of the exposure. We investigated whether exposure dynamics affect species sensitivity of five fish species and if their sensitivity rankings differ among exposure profiles. We calibrated compound- and species-specific reduced general unified threshold models of survival (GUTS-RED) models from standard laboratory toxicity data. Using the calibrated models, we generated species sensitivity distributions based on median lethal profile multiplication factors for three characteristic exposure profiles. The sensitivity rankings of the fish species changed as a function of exposure profile. For a multiple-peak scenario, rainbow trout was the most sensitive species. For a single peak followed by a slow concentration decline the most sensitive species was the fathead minnow (GUTS-RED-stochastic death) or the common carp (GUTS-RED-individual tolerance). Our results suggest that a single most sensitive species cannot be defined for all situations, all exposure profiles, and both GUTS-RED variants. (link to paper)

Predicting Mixture Effects over Time with Toxicokinetic–Toxicodynamic Models (GUTS): Assumptions, Experimental Testing, and Predictive Power

Current methods to assess the impact of chemical mixtures on organisms ignore the temporal dimension. The General Unified Threshold model for Survival (GUTS) provides a framework for deriving toxicokinetic–toxicodynamic (TKTD) models, which account for effects of toxicant exposure on survival in time. Starting from the classic assumptions of independent action and concentration addition, we derive equations for the GUTS reduced (GUTS-RED) model corresponding to these mixture toxicity concepts and go on to demonstrate their application. Using experimental binary mixture studies with Enchytraeus crypticus and previously published data for Daphnia magna and Apis mellifera, we assessed the predictive power of the extended GUTS-RED framework for mixture assessment. The extended models accurately predicted the mixture effect. The GUTS parameters on single exposure data, mixture model calibration, and predictive power analyses on mixture exposure data offer novel diagnostic tools to inform on the chemical mode of action, specifically whether a similar or dissimilar form of damage is caused by mixture components. Finally, observed deviations from model predictions can identify interactions, e.g., synergism or antagonism, between chemicals in the mixture, which are not accounted for by the models. TKTD models, such as GUTS-RED, thus offer a framework to implement new mechanistic knowledge in mixture hazard assessments. (open access link)

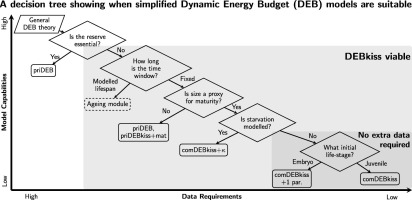

Sublethal effect modelling for environmental risk assessment of chemicals: Problem definition, model variants, application and challenges

Bioenergetic models, and specifically dynamic energy budget (DEB) theory, are gathering a great deal of interest as a tool to predict the effects of realistically variable exposure to toxicants over time on an individual animal. Here we use aquatic ecological risk assessment (ERA) as the context for a review of the different model variants within DEB and the closely related DEBkiss theory (incl. reserves, ageing, size & maturity, starvation). We propose a coherent and unifying naming scheme for all current major DEB variants, explore the implications of each model's underlying assumptions in terms of its capability and complexity and analyse differences between the models (endpoints, mathematical differences, physiological modes of action). The results imply a hierarchy of model complexity which could be used to guide the implementation of simplified model variants. We provide a decision tree to support matching the simplest suitable model to a given research or regulatory question. We detail which new insights can be gained by using DEB in toxicokinetic-toxicodynamic modelling, both generally and for the specific example of ERA, and highlight open questions. Specifically, we outline a moving time window approach to assess time-variable exposure concentrations and discuss how to account for cross-generational exposure. Where possible, we suggest valuable topics for experimental and theoretical research. (Link to paper)

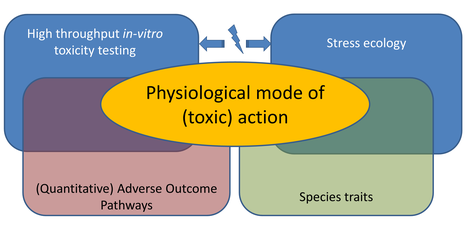

Physiological modes of action across species and toxicants: the key to predictive ecotoxicology

Ecotoxicologists need tools to identify those combinations of man-made chemicals and organisms most likely to cause problems. In other words: which of the millions of species are

at risk from pollution? And which of the tens of thousands of chemicals contribute most to the risk? We identified our poor knowledge on physiological modes of action (how a chemical affects the

energy allocation in an organism), and how they vary across species and toxicants, as a major knowledge gap. We also find that the key to predictive ecotoxicology is the systematic, rigorous

characterization of physiological modes of action because that will enable more powerful in vitro to in vivo toxicity extrapolation and

in silico ecotoxicology. In the near future, we expect a step change in our ability to study physiological modes of action by improved, and partially automated,

experimental methods. Once we have populated the matrix of species and toxicants with sufficient physiological mode of action data we can look for patterns, and from those patterns infer general

rules, theory and models. (open access, link to paper at ESPI)